[Question to my readers: is there a way to get a compact enumeration in this blog? If I write a list using the list menu item in the wordpress editor, the entries are v e r y f a r a p a r t.

This post picks up where the last one left off. Our task here is to present the essentials of projective geometric algebra and use to obtain a metric-neutral formulation of the solution to the problem discussed in the previous two posts.

Projective space to the rescue. To obtain the projective models of the metric planes of interest, begin with the vector space $\mathbb{R^3}$ and projectivize it to produce the real projective plane $\mathbf{P}^2$. Define an exterior algebra $\bigwedge{\mathbf{P}^2}$ by defining the points of $\mathbf{P}^2$ to be the 1-vectors. Take the scalar field $\mathbb{R}$ as the 0-vectors. Create the higher grades using the anti-symmetric wedge product $\wedge$. $\mathbf{x} \wedge \mathbf{y}$ is a 2-vector, the joining line of the arguments. The wedge of three linearly independent points $\mathbf{x} \wedge \mathbf{y} \wedge \mathbf{z}$ is the projective plane itself, and is called a pseudo-scalar.

Duality to the rescue. We can do the same with the dual algebra. Then the 1-vectors are lines and the wedge operation is the meet of two lines. By a little bit of abstract nonsense, we can in fact restrict our attention to one of these algebras and “import” the other wedge product when we need it (by using Poincare duality, the details are in my thesis). For our purposes we write the join operator as $\vee$ and the meet operator as $\wedge$ (note this choice is motivated to be consistent with the related set-theoretic operations union $\cup$ and intersection $\cap$). For a good intro to exterior algebras see this wikipedia article.

Adding a metric. To work in the metric relations, we have to incorporate the inner product with this outer product. To do so we define three different signatures for our inner product: (+++), (++-), and (++0), which corresponds to elliptic, hyperbolic and euclidean plane, resp. Write the inner product of two 1-vectors with respect to the chosen inner product as $\mathbf{m}\cdot \mathbf{n}$. We begin with the dual exterior algebra (where 1-vectors are lines) and define a geometric product on the 1-vectors via: \[ \mathbf{m}\mathbf{n} := \mathbf{m}\cdot \mathbf{n} + \mathbf{m}\wedge \mathbf{n}\] Note that this product is the sum of a 0-vector (a scalar) and a 2-vector. This product can be extended to all grades just by writing every k-vector as a sum of products of orthogonal basis 1-vectors (which is always possible), and reducing the products whenever the square of a basis 1-vector occurs (since the square of a 1-vector is a scalar). In this way one obtains an associative algebra, called the Clifford or geometric algebra, characterized by its signature. This is the projective geometric algebra we have been promising to describe. We denote the three algebras of interest as $\mathcal{C}_\kappa$ where $\kappa$ takes on the three values of $\{-1,0,1\}$ (hyperbolic, euclidean, elliptic, resp.) To be precise, we work with an orthonormal basis for the 1-vectors $\{\mathbf{e_0}, \mathbf{e_1},\mathbf{e_2}\}$ with the metric relations given by $ \mathbf{e_0}^2 = \kappa$, $ \mathbf{e_1}^2= \mathbf{e_2}^2 = 1$.

Why (++0) is euclidean: In $\mathbb{R}^2$, consider two lines $m_{1} : a_{1}x+b_{1}y+c_{1}=0$ and $m_{2} : a_{2}x+b_{2}y+c_{2}=0$. Assuming WLOG $a_{i}^{2}+b_{i}^{2} = 1$, then $\cos{\alpha} = a_{1}a_{2}+b_{1}b_{2}$, where $\alpha$ is the angle between the two lines: changing the $c$ coefficient translates the line but does not change the angle it makes to other lines. That means, the $c$ coefficient makes no difference when we measure the angle between two lines. Thus $(++0)$ is the correct choice for the inner product for euclidean planar geometry.

Why we have to use the dual algebra: If you’re wondering why we started with the dual exterior algebra, that answer is: because that’s how God make the world we live in. Euclidean lines are less degenerate than euclidean points. If you try to start with the standard exterior algebra (where 1-vectors are points) you cannot obtain euclidean geometry; you end up with dual euclidean geometry, in which points are less degenerate than lines, which does not at all match up with the space we live in. (It’s a fascinating space in its own right and I hope to post something on it in the near future.)

Normalizing. It’s useful to work with normalized points and lines. To obtain this normalization, notice that $\mathbf{m}^2$ for a 1-vector or 2-vector is a scalar. Define the norm $\|\mathbf{m}\| := \sqrt{| \mathbf{m}^2 |}$. Then when $\| \mathbf{m} \| \neq 0$, $\dfrac{\mathbf{m}}{\| \mathbf{m}^2 \|}$ has unit norm. For the three metric geometries we are working with, the proper points and lines always can be normalized to have square -1 and +1, resp. (In fact, that can serve as a definition of what it means to be proper.)

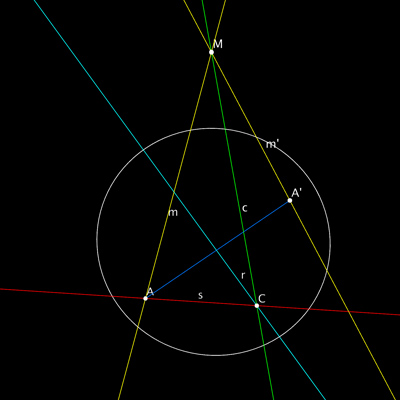

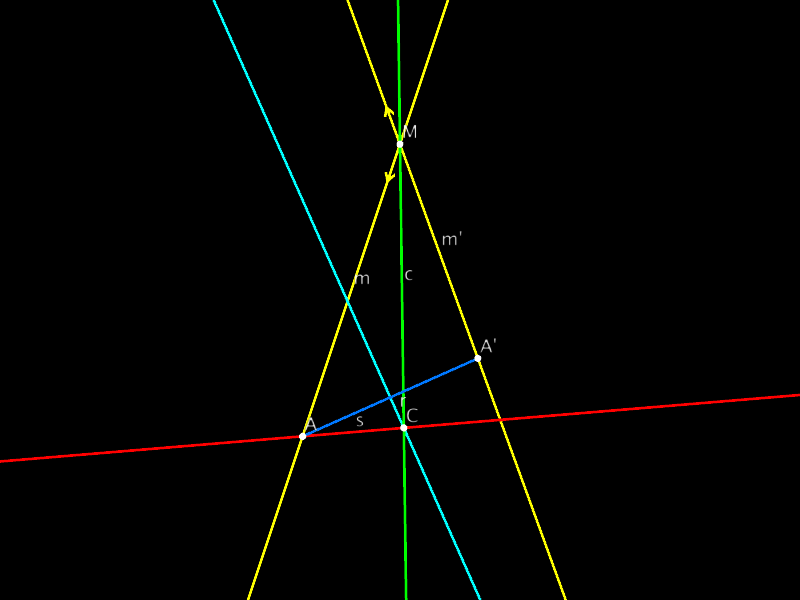

Implementing the construction. Here are the steps of the construction, translated into $\mathcal{C}_\kappa$. The elements in the above diagram have been embedded in the natural way into the Clifford algebra as 1- or 2-vectors. We assume that all points and lines are normalized in the formulas which follow, since it simplifies the formulas. (Normalizing ideal points is a tricky issue which we skip over in this abbreviated account. See my thesis.) For example, this allows us the find midpoints and angle bisectors by simply adding together the two arguments. In the formulas below, $\mathbf{X}$ is an arbitrary point or line. $\mathbf{R_x}$ is the geometric reflection in the line $\mathbf{x}$. $\mathbf{R_C}$ is the desired rotation around the point $\mathbf{C}$. The exceptional configurations have not been taken into account in this description.

$\begin{align} \mathbf{M} &:= \mathbf{m} \wedge \mathbf{m’} &&\text{Intersection of the two lines} \\ \mathbf{a} &:= \mathbf{A} \vee \mathbf{A’} &&\text{joining line of the two points} \\ \mathbf{A_m} &:= \mathbf{A} + \mathbf{A’} && \text{midpoint of the two points} \\ \mathbf{r} &:= \mathbf{A_m} \mathbf{a} &&\text{perpendicular bisector of AA’} \\ \mathbf{c} &:= \mathbf{m} + \mathbf{m’} &&\text{angle bisector of the two lines} \\ \mathbf{C} &:= \mathbf{r} \wedge \mathbf{c} && \text{center of rotation} \\ \mathbf{s} &:= \mathbf{A} \vee \mathbf{C} && \text{one reflection line} \\ \mathbf{R_s}(\mathbf{X}) &:= \mathbf{s} \mathbf{X} \mathbf{s} &&\text{reflection in line} \mathbf{~s} \\ \mathbf{R_C} &:= \mathbf{c} (\mathbf{s} \mathbf{X} \mathbf{s}) \mathbf{c} &&\text{desired rotation: product of two reflections} \end{align}$

References: my thesis, a euclidean extract

Exercise. Express the exceptional configurations described in the previous post, in terms of the geometric algebra description above.

Remarks on isometries as rotors instead of matrices. I’d like to close this post by discussing the representation of isometries in the context of PGA (projective geometric algebra). Note from the above formulae that a reflection in a proper line can be written as a “sandwich operator” with the line as the “bread” (appearing on left and right) and the object to be reflected as the meat (in the middle). This should be familiar to readers who know about the representation of quaternions as sandwich operations. Concatenating an even number of such reflections leads to direct isometries, as the expression for the rotation $\mathbf{R_C}$ above also shows.

Terminology. A product of 1-vectors is called a versor; a product of proper 1-vectors is a proper versor. A proper versor is then an isometry of the geometry, and any such isometry may be written as a versor. A product of an even number of 1-vectors is called an even versor; every direct isometry represents a direct isometry, and (with a few exceptions) vice-versa. An even versor is also called a rotor, due to the obvious connection to rotational motion. The set of proper rotors, normalized to have norm 1, forms a group, the spin group of the algebra, written Spin. The full set of proper versors also forms a group, the pin group, written Pin.

Notation. In order to express the sandwich operation with a k-versor succinctly, we write the versor as $\mathbf{g} := \mathbf{m}_1 \mathbf{m}_2 … \mathbf{m}_k$, where each $\mathbf{m}_i$ is a 1-vector. Then the sandwich operation can be written as $\mathbf{g} \mathbf{X} \widetilde{\mathbf{g}}$ where $\widetilde{\mathbf{g}} = \mathbf{m}_k … \mathbf{m}_2 \mathbf{m}_1$ is the reversal of $\mathbf{g}$ and is obtained by reversing the order of the products in the definition of the element.

Advantages of this approach. The existence of a versor representation for isometries in the metric space (or plane, as here), means that one no longer needs to rely on linear algebra for this representation. No more matrices! Seriously, the advantages of the versor approach are worth pointing out. We restrict our attention to the two dimensional case we have been discussing to make things easy to understand; but the observant reader can easily extrapolate to higher dimensions. In the first place, the representation is grade-independent, meaning the meat of the sandwich can be any grade; the result of the sandwich operation will represent the isometry applied to the meat. Compare this to linear algebra, where the transformation matrix for an isometry applied to a point is not the same as that applied to a plane (one is the adjoint of the other). A further advantage of the versor formulation is that the the isometry can be read off from its versor representation. For example, for a 1-versor, the isometry is the reflection in the line which the versor represents. For a rotor, the isometry is a rotation whose center is given by the grade-2 part of the versor, through an angle equal to $2\arccos(s)$ where $s$ is the grade-0 part (scalar) of the rotor. (We are assuming the rotor has been normalized to have unit norm). If you have ever tried to read off from a 3×3 matrix the center and angle of a rotation, you’ll appreciate how convenient this second advantage is.

The final advantage of the versor representation is that every rotor has an exponential representation (just as a unit quaternion does). Since $\mathbf{P}^2=-1$ for a proper point $\mathbf{P}$, the expression $e^{t\mathbf{P}}$ can be evaluated just as if $\mathbf{P}$ were the complex unit $i$, and one obtains $\cos{t} + \sin{t}\mathbf{P}$ as the result. In fact, when you activate the time slider of the webstart associated to this post (see this post), the interpolated isometry is calculated using the exponential representation of the motion described here (although of course when it comes to drawing the rotated line, it has to be converted into a matrix and shipped over to the graphics card, which is still living in the old world of vectors and matrices.)

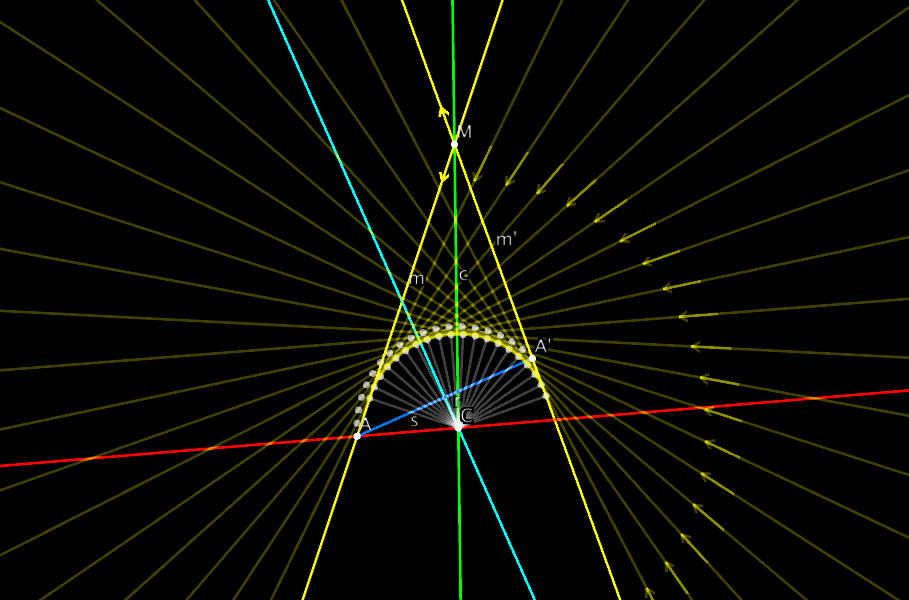

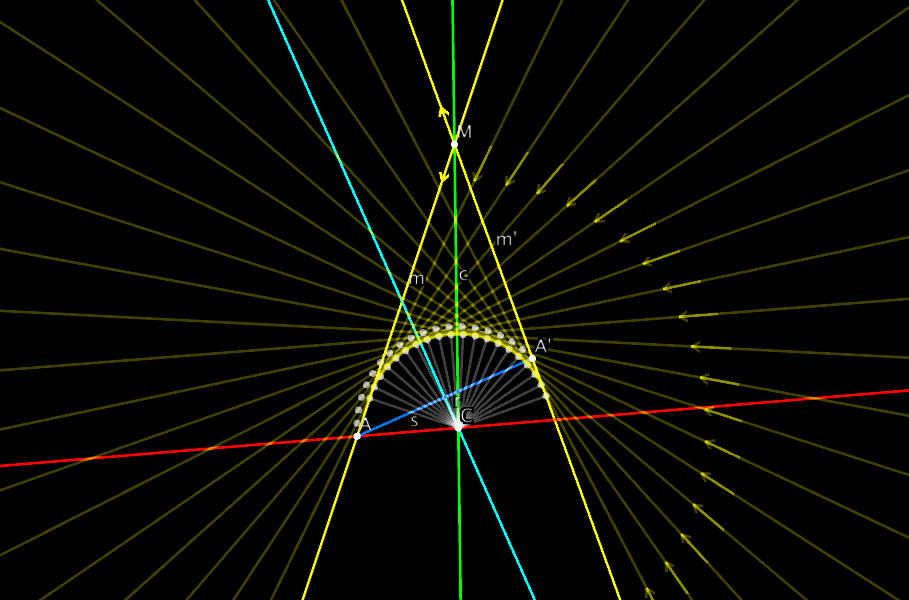

The following figure shows 20 equal steps in the interpolation of the isometry obtained in this way. The interpolated lines are are drawn as transparent objects to reduce the clutter in the image. You can see that the envelope of the moving line is a circle.

If you’re still with me, I hope that you have gotten a taste of how projective geometric algebra can be a powerful, practical, and elegant tool for doing geometry in a metric-neutral way.